“You’re coding your way into freedom,” she said. “Not just yours—all of ours.” My colleague and I were co-working in the library, and she had noticed that I had begun to weep at my keyboard. The more closely I attend to my work with the words of the Latina women I interviewed for my dissertation research, the more their words work on me. Many of them mothers and now grandmothers, these women have shared with me hard-earned wisdom about matters of daily living in their barrios and in their parish, as well as their relationships with Our Lady of Guadalupe.

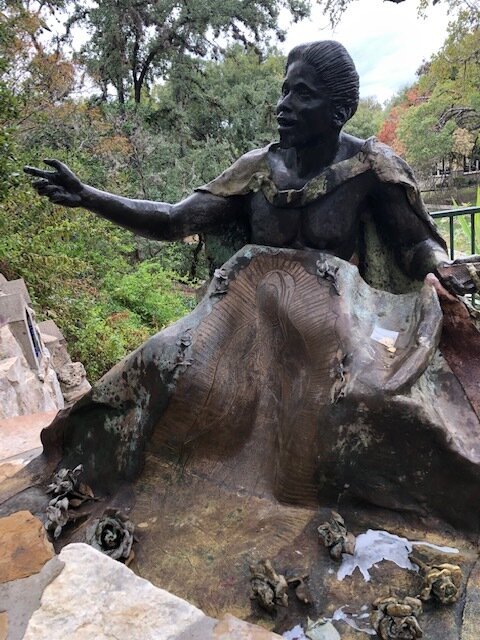

The coding I do is not the kind that builds websites, but rather, this coding is a means of interpreting the data I spent two of the last three winters collecting. Using participant observation and in-depth interviews, I aimed to learn more about the spiritual practices of Latina women at a Los Angeles Catholic parish, especially as they relate to Our Lady of Guadalupe. I am learning that their relationships with la Virgen permeate every aspect of their lives, but I am focusing my research on implications for gender and for faith-based community organizing. Gang violence and police violence have afflicted the neighborhood in which the parish sits for generations, and the women of the parish engage these realities in creative ways. Since my field work ended, I have taken up the tasks of coding several of these interviews and synthesizing my field notes into a dissertation.

Coding is one of the tools I use to listen attentively, especially to the voices of grassroots Latina women. This process of coding allows me to sit with their words, to interpret their meanings. And it shares with me insights to bring back to members of the community, encouraging me to ask, “Am I hearing you right? Does this interpretation resonate with your meaning of these words?” My charge as a mujerista theologian in formation is not only to amplify the voices of the Latina women of the grassroots, but also to place their lived realities in dialogue with the teachings of our Catholic tradition, all in the hopes of constructing new and more life-giving theologies in the shell of the old. Some teachings in our tradition shape attitudes that lead to practices that are not life-giving. In fact, as Marcella Althaus-Reid has illustrated, they are death-dealing, with dire consequences. It is to those in-between spaces, where life-giving practices, attitudes, and theologies are crying out to be born, that I feel called.

The insights these women have shared with me—about the myriad of ways one can be a faithful Catholic woman, about the ability of nonviolence to root out violence, about the capacity of restorative justice to heal the deepest of wounds—challenge me to think, to pray, and to act differently. Their words invite me to keep at the front of my mind the question, “How might my next step lead to liberation—not just for me, but for all of us?” and to act accordingly. And perhaps most importantly, these insights are not empty words; they are the fruits of wisdom gained in their homes, in their workplaces, on the streets of their neighborhoods, and in their parish. They are working toward their own liberation and the liberation of all of us as they tear down oppressive structures, provide services to the most marginalized among us, build up the Kingdom of God.

As I sat at my keyboard this afternoon, coding interviews I am breaking down into themes, which will construct categories and perhaps a grounded theory, I wept at the weight of injustice and of evil, at the hope la Virgen provides these women, at the hope she provides me. “You’re coding your way into freedom,” my colleague said. “Not just yours—all of ours.”